|

After a busy Mother’s Day on Sunday, Alicia Dassa had already gone to bed when her husband asked their 18-year-old son to move their car to a spot that had opened in front of their house on 51st Avenue South in Seattle’s Rainier Beach neighborhood. She heard gunshots. “That’s normal around here,” Dassa said of her neighborhood. “I didn’t even get out of bed.” But then a neighbor ran into her house and told her that her son, Conner Dassa-Holland, had just been shot. Alicia Dassa raced outside in her nightshirt and saw her car stuck atop a small rock wall. Her husband, James, was holding their son and screaming her name.

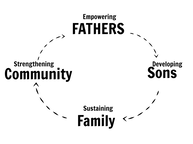

“I saw Conner and I just grabbed him and was holding him,” Alicia Dassa said this week in a phone interview. “I just held him and told him it was going to be OK and that we loved him. He still had a pulse, a strong pulse, when the ambulance arrived.” Her son didn’t make it. Alicia and James Dassa had to break the news to 30 family members and friends who, because of the coronavirus pandemic, weren’t allowed inside Harborview Medical Center and so had gathered on a sidewalk outside the hospital. “I got to hold him and be with him and he wasn’t alone,” said Alicia Dassa, reflecting on the last moments she had with Conner before paramedics whisked him away. “We got to be with our boy and I feel so blessed to have had that.” On Tuesday, 300 people attended a vigil outside the family’s house. The Seattle Police Department closed the street to traffic. Dassa, a county employee, used the event as a call to action, convinced whoever killed her son grew up without the love and support she and her husband have poured into their five children, ages 8 to 24. “We have to do better as a community. We have to understand this is not an issue of race — it’s an issue of sadness and poverty and broken families and not enough resources and all the things that get kids on a path that turns out bad,” she said. Dassa is white and her husband, who works for Chateau Ste. Michelle Winery, is Black. Dassa-Holland was white, and his four siblings are mixed race. The family moved to Rainier Beach in 2011 because it is a neighborhood “where other families look like us,” Dassa said. “We really wanted the kids to grow up in an area where they’d learn from the people around us,” she said. “It didn’t just shape who we are as a family, but who the kids are as people.” Larry Wilmore, a night supervisor at the Safeway grocery store less than 1,000 feet north of the Dassa family home, was working Sunday night when he heard three gunshots and called 911. He didn’t learn until the next morning it was Dassa-Holland who had been killed. Last summer, Dassa-Holland worked with Wilmore at Safeway before starting his freshman year at the University of Washington. “I was in disbelief, as I am now. Total disbelief,” said Wilmore. “I think the fact Conner wasn’t running with gangs or doing all that is why it’s super hard to believe that it happened. The whole neighborhood is in disbelief and there’s anger that it keeps happening.” After a spike in violence nine years ago that saw 10 people gunned down in South Seattle within a span of three to four months, seven of them in proximity to the Rainier Beach Safeway, Wilmore started Fathers And Sons Together (FAST), an organization aimed at strengthening fathers’ relationships with their children as a way to prevent youth involvement in the criminal justice system. FAST hosts basketball and baseball camps, overnight camping trips, fishing excursions, barbershop events and dad-and-daughter days for kids ages 5 and up. When fathers are involved in their children’s lives, kids perform better academically and make better life choices, said Wilmore. Organizations like FAST need more funding and support from local government, he said. “I really believe the violence in the area needs to stop. Self worth and respect for other people will keep a kid from shooting a person for no reason,” Wilmore said. “That’s what the difference is going to be, with people with their feet on the ground, who know the community and are working hard to make changes.” Wilmore said the community won’t find any sense of closure until Dassa-Holland’s killer is apprehended. “Kids are walking around saying, ‘Wow, what happened? Who’s next?’ They’re shellshocked,” he said. Like Wilmore, Chukundi Salisbury, a longtime community activist and Seattle Parks and Recreation employee, woke up Monday morning to the news of Dassa-Holland’s killing. Salisbury has known the Dassa family for years. “What we have to do is really engage young people in a real way. I feel that’s what’s going to change our community and everybody has to look at it like it’s their job,” Salisbury said. “Until we see other people’s kids as worthy of our engagement, we’re going to have issues like this, we’re always going to have incidents like this. It’s an ongoing struggle.” He said Dassa-Holland was committed to making his community better. “He was definitely ready to step up and be a leader,” said Salisbury. “This is a great kid and we’re not going to chalk (his killing) up to gang violence.” Sgt. Lauren Truscott, a spokeswoman for the Seattle Police Department, said the investigation into Dassa-Holland’s homicide is ongoing. She asked anyone with information to contact the homicide unit’s tip line, 206-233-5000. The King County Medical Examiner’s Office determined Dassa-Holland died from a gunshot wound to the head. Dassa recalled the morning her son called her last year and announced he was running for senior class president at Rainier Beach High School. She asked if he wanted her to pick up campaign supplies but he told her no. The election was that day. “He said, ‘Nah, I got this.’ Kids had been campaigning for weeks. He gave a speech and he won. I heard it was pretty impressive,” she said of Dassa-Holland, who graduated last June. There were a lot of impressive things about Dassa-Holland: He was a captain of his high school football team and a volunteer track coach. He mentored younger kids and counseled his peers on suicide prevention. He watched YouTube videos to learn how to braid his little sister’s hair. He was an honor student who applied to 19 universities and was accepted at all of them. He studied prelaw at the UW and planned to spend his legal career working on social-justice issues and advocating for people in the neighborhood where he grew up. He and his girlfriend, an aspiring FBI agent, were a power couple in the making, Dassa said. “He didn’t talk a lot but when he did, it was hilarious or really smart,” she said of her son, who would have turned 19 on May 31. “When he listened to you, he really listened and you could really feel it.” Though still in early planning stages, Dassa said her family and other community members are working to develop a violence-prevention campaign, focused on intervening in the lives of kids in the neighborhood. “Conner grew up here, he played sports here, he volunteered here. He was Rainier Beach,” she said. “The love and support we’ve gotten from the community is the only reason we’re upright and breathing.” News researcher Miyoko Wolf contributed to this story. Sara Jean Green: 206-515-5654 or [email protected]; on Twitter: @SJGTimes.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

June 2023

Categories |

Because this relationship MATTERS! |

|

Quick Links |

© Fathers and Sons Together. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed